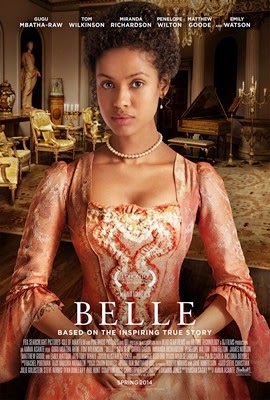

Review: Belle (2014)

I’ve long been fascinated with the story of Dido Elizabeth

Belle ever since I read a blog post by author Janet Mullany at the History

Hoydens blog several years ago. For a

while I even contemplated trying to fictionalize the story. So I was very excited when I heard that she

was going to be the subject of a major motion picture. This film opened in the US in limited release

last Friday, and since delayed gratification isn’t really my thing, I went to

see the film on Sunday at one of the only two movie theatres showing it in the

city.

However, before seeing the film, I picked up a copy of Paula

Byrne’s new book entitled Belle: The Slave Daughter and the Lord Chief Justice. Although Belle’s name is in the title, the

book is more about her great uncle Lord Mansfield and the era in which she

lived than it is an actual biography.

The reason being that very little is known about Belle.

The simple facts are these: She was born sometime in 1761 to Sir John

Lindsay, nephew of Lord Mansfield and a slave named Maria. At some point, her father brought her to

Kenwood to be raised alongside her cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray. The assumption is made that Belle’s mother

died at some point, we don’t know when.

We do know that it was highly unusual for a man of Sir John Lindsay’s

standing to want his illegitimate daughter (white or black) to be brought up by

his family. The book details the Zong

case which is a key plot point in the film, a brief history of the abolitionist

movement in England, as well as information about what life was like for London’s

black residents. Apparently at the time

that Belle lived, there were 15,000 blacks living in the UK. Some were slaves, but most were free. Interracial marriage was unusual but not

unheard and not illegal as long as the couple was of equal status. So for example, a black footman could marry a

maid, but not a cook, because the cook would have been of higher status.

The film opens in 1769.

John Lindsay (Matthew Goode), who is in the Royal Navy, comes to a port

city after learning of the death of Belle’s mother. Since he spends so much time at sea, he

decides to drop her off at Kenwood, the home of his uncle, William Murray, 1st

Earl of Mansfield (Tom Wilkinson), and his wife Elizabeth (Emily Watson). The couple is initially reluctant to take her

in, given that she is black. They worry about how it might look. However, they

realize that she might make a good companion for their other great niece

Elizabeth, who has been dropped off by her father after her mother’s

death. So Dido has a new home.

Years pass although we are not told how many have gone by. Dido (Gugu Mbatha-Raw) and Elizabeth grow up

to be besties, sharing a room, and studying together. However, Dido is beginning to be aware that

things are different for her because of the color of her skin. When company comes, Dido has to eat in the lady’s

parlor not with the guests, although she is allowed to have coffee in the drawing

room. Even the news that her father has

died and left her £2,000 a year (a substantial sum) doesn’t change her status

all that much.

The film does an excellent job of portraying how few choices

women had back in the 18th century.

Marriage was still a transaction, although there were couples who did

marry for love, but that wasn’t the overriding concern. Dido’s cousin,

Elizabeth, has to marry well because she has no dowry but she also hopes to

marry for love. Their aunt Mary (Penelope

Wilton) tells them about her own thwarted love affair with a man who had no

fortune. For Lord and Lady Mansfield, Dido’s inheritance means that they don’t

have to worry about what will happen to her after they are dead. They are aware that Lord Stormont, the heir,

will not be as open-minded about Dido living at Kenwood. One of the saddest moments in the film is a

scene where Lady Murray tells Elizabeth that she is to have a London season,

while Dido is told by her uncle that upon their return from London she is to

take over the role of housekeeper from her Aunt Mary. There will be no London season for Dido

despite her wealth.

The divide between the two girls is further illustrated when

Lady Ashford (Miranda Richardson) and her two sons come for dinner. The elder James (played by Tom Felton) is not

only a snob but also a racist who is disgusted that his brother Simon finds

Dido attractive. Lady Ashford is

prepared to overlook Dido’s color and her illegitimacy because of the money. Dido, flattered by the attention, initially

agrees to engagement with James but her growing interest in the Zong case and

her attraction to a young law student John Davinier open her eyes to the world

outside of Kenwood House. There is an

awkward moment when the family travels to London for the season. One of the maids, Mabel, is black. Dido

questions her uncle as to whether Mabel is a slave or a free woman. Dido also feels uncomfortable around her

because of the difference in their stations.

The film is sumptuously shot, the acting is impeccable and I

admit that I teared up on more than one occasion during the film. It’s not

often that I forgive a film for taking historical liberties but Belle was so

moving in depicting the story of this young black woman stuck between two

worlds, not really part of either one, that I’m giving it a pass. Some critics have compared the film to Sense

and Sensibility and the director admits that is feeling that she intended to

invoke, particularly in the friendship between Elizabeth and Dido. Dido is the more practical of the two, much

more careful with her emotions, no doubt because of her status. While Elizabeth, on the other hand, is all

feeling. She barely knows James Ashford

yet she falls head over heels for him, and is devastated when she discovers

that he is engaged to another woman. An

argument between Dido and Elizabeth echoes the argument that Eleanor and

Marianne have in S&S about Eleanor hiding her feelings toward Edward

Ferrers. In Belle, Dido and Elizabeth

argue about James Ashford. Dido tries to

warn Elizabeth that James is an asshole (he assaults Dido at a garden party)

but Elizabeth refuses to hear her.

In the 21st century, it's rare to have a historical film about a black woman, written by a black woman (Misan Sagay) and directed by a black woman (Amma Asante). I highly recommend this film for anyone interested in seeing

a different side of 18th century England.

Now for a little Fact vs. Fiction:

1 1) Dido was known as Dido Elizabeth Lindsay –

Fiction. Although in the film she uses her

father’s last name Lindsay, in real life Dido was known as Dido Elizabeth

Belle. Since she was illegitimate, she

would have had no right to use Lindsay.

3) Dido married a lawyer named John Davinier –

Fiction – While Dido did marry John Davinier, it was after her uncle’s death

when she was in her thirties. Davinier was

a Frenchman, probably one of many who fled the revolution in France. Historians don’t know what kind of servant he

was. It is possible that he worked for Lord Mansfield’s nephew and heir, Lord

Stormont. What we do know is that they

had two sons, and lived in Pimlico. Dido

died in 1804 when she was in her early forties.

Unfortunately her grave has been lost to us.

4 4) The Zong massacre, which occurred in 1781, is a

major plot point in the film. The owners

of the Zong claimed that they forced to kill several of the slaves because of

inadequate water supplies. Dido tells John Davinier that the ship had plenty of

chances to stop and replenish their water supply but didn’t. However, that is not precisely what

happened. The reality is that the ships

water supply was replenished because it had rained for several days, before the

killing was finished. Not all of the

slaves on board were massacred. Over two

hundred slaves were still on board the ship when it finally arrived in Jamaica.

People were worried that Lord Mansfield’s judgment might have been affected by

his relationship with Dido, although as he makes clear in the film, he was

always able to separate the personal from the professional. For example, as a youth Mansfield had

supported the Old Pretender James III.

This did not keep him from prosecuting the leaders of the Jacobite

rebellion in 1745.

Comments