Was Aemilia Bassano Lanier Shakespeare’s Dark Lady? - Guest Post by Mary Sharratt

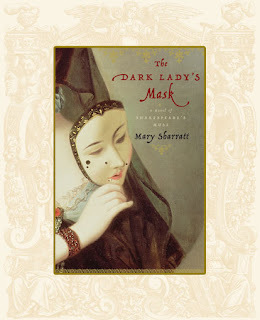

Scandalous Women is pleased to welcome author Mary Sharratt to the blog today to talk about Aemilia Bassano Lanier, the heroine of her new novel The Dark Lady's Mask,

Born in 1569, Aemilia Bassano Lanier (also spelled

Lanyer) was the highly cultured daughter of an Italian court musician—a man

thought to have been a Marrano, a secret Jew living under the guise of a Christian

convert.

After her father’s death, seven-year-old Aemilia was

fostered by Susan Bertie, the Dowager Countess of Kent, who gave her young

charge the kind of humanist education generally reserved for boys in that era.

Later, after Bertie remarried and moved to the Netherlands, Aemilia became the

mistress of Henry Carey, Lord Chamberlain to Queen Elizabeth. As Carey’s

paramour, Aemilia Bassano enjoyed a few years of glory in the royal court—an

idyll that came to an abrupt and inglorious end when she found herself pregnant

with Carey’s child. She was then shunted off into an unhappy arranged marriage

with Alfonso Lanier, a court musician and scheming adventurer who wasted her

money. So began her long decline into obscurity and genteel poverty, yet she

triumphed to become a ground-breaking woman of letters.

Aemilia Bassano Lanier was the first English woman to

aspire to a career as a professional poet by actively seeking a circle of

eminent female patrons to support her. She praises these women in the

dedicatory verses to her epic poem, Salve

Deus Rex Judaeorum, a vindication of the rights of women couched in

religious verse and published in 1611.

But was Lanier also the mysterious Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s

sonnets, as the late A. L. Rowse famously proclaimed?

Is this Aemilia Bassano Lanier? Miniature by Nicholas Hilliard.

Shakespeare’s Dark Lady Sonnet Sequence (sonnets

127-152) describes a woman with an “exotic” dark beauty that sets her apart

from the pale English roses. Musically gifted, she plays the virginals like a

virtuosa, winning the poet’s heart. She is also of tarnished reputation—a woman

of bastard birth and a married woman who lures the likewise married Shakespeare

into a shameful, doubly-adulterous affair. Alas, the lady proves capricious and

unfaithful, and the bitter end of their affair leaves her poet-lover roiling

with disgust. Shakespeare describes her as “my female evil.”

William Shakespeare

Over the centuries Shakespearean scholars have tried

to deduce the Dark Lady’s identity. Candidates include Lucy Morgan, a London

brothel owner of African ancestry; and Sara Fitton, lady-in-waiting to

Elizabeth I.

Aemilia Bassano Lanier herself seems to fit the bill.

A woman of Italian-Jewish heritage, it’s plausible that she had raven-black

hair and an olive complexion. Her parents’ common-law marriage meant that she

was officially classed as a bastard. The illegitimate son she had with the Lord

Chamberlain did nothing to shore up her reputation. As a court musician’s

daughter and later another court musician’s unwilling wife, it’s likely that

she was musically accomplished and a deft hand at the virginals. After being

jilted by the Lord Chamberlain and thrust into a forced marriage with a man she

detested, she may well have been tempted to look for love elsewhere. The Lord

Chamberlain, interestingly enough, was also Shakespeare’s patron, the money

behind his theatre company, Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

However, none of this proves that Lanier was the Dark

Lady, or even that there was a Dark

Lady. Academic scholars will point out that we don’t even know if Shakespeare’s

sonnets were autobiographical. Lanier scholars in particular find the Dark Lady

question an unwelcome detraction from Lanier’s own considerable literary

achievements.

Having established these facts, I must confess that as

a novelist I could not resist the allure

of the Dark Lady myth. As Kate Chedgzoy points out in her essay “Remembering

Aemilia Lanyer” in the Journal of the

Northern Renaissance, this myth endures because it draws on “our continuing

cultural investment in a fantasy of a female Shakespeare.”

My intention was to write a novel that married the

playful comedy of Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard’s Shakespeare in Love to the unflinching feminism of Virginia Woolf’s

meditations on Shakespeare’s sister in A

Room of One’s Own. How many more obstacles would an educated and gifted

Renaissance woman poet face compared with her ambitious male counterpart?

In The Dark

Lady’s Mask, I explore what happens when a struggling young Shakespeare

meets a struggling young woman poet of equal genius and passion. If Lanier and

Shakespeare were lovers, would this explain how Shakespeare made the leap from

his history plays to his Italian comedies and romances—the turning point of his

career? Lanier, after all, was an Anglo-Italian trapped in a miserable arranged

marriage. The names Aemilia, Emilia, Emelia, and Bassanio all appear in

Shakespeare’s plays. His Italian comedies are set in Veneto, Lanier’s ancestral

homeland. What if Shakespeare’s early comedies were the fruit of an active

collaboration between him and Lanier?

I find it fascinating how the strong, outspoken women

of Shakespeare’s early Italian comedies, such as the crossdressing Rosalind in As You Like It and the spirited Beatrice

in Much Ado About Nothing, gave way

to much weaker heroines and misogynistic portraits of women in Shakespeare’s

great tragedies, such as frail, mad Ophelia in Hamlet. This change in tack leads me to wonder if the historical

Shakespeare actually did have a bittersweet affair with a mysterious, unknown

woman that cast a shadow over his later life and work.

Most intriguingly, Lanier’s own proto-feminist Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum was published

in the wake of Shakespeare’s sonnets bitterly mocking his Dark Lady. If she and

Shakespeare were estranged lovers, was this her spirited riposte to his

defamation of her character? Did the woman Shakespeare maligned as his “female

evil” pick up her pen in her own defense and in defense of all women?

These two poets had such radically different character

arcs. We all know about Shakespeare’s rise to the glory that would enshrine him

as an enduring cultural icon. But there was no meteoric rise for Lanier. Though

she eventually triumphed to become a published poet, she died in obscurity and

has only recently been rediscovered by scholars.

In my novel I wanted to redress the balance by writing

Aemilia Bassano Lanier back into history. Her life and work stand in direct

opposition to Virginia Woolf’s pronouncement in “A Room of One’s Own” that “it would have been . . .

completely and entirely impossible, for any woman to have written the plays of

Shakespeare in the age of Shakespeare.” Although Lanier may not have been a

playwright, her achievement as a poet speaks for itself. Whether or not she was

Shakespeare’s Dark Lady, muse, lover, or collaborator, she has certainly earned

her place in history as Shakespeare’s peer.

Mary Sharratt’s novel, The Dark Lady’s Mask: A Novel of

Shakespeare’s Muse, is published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Visit her

website: www.marysharratt.com.

Comments